I’m in Finland for the “Towards A Science of Consciousness” Conference at the University of Helsinki.

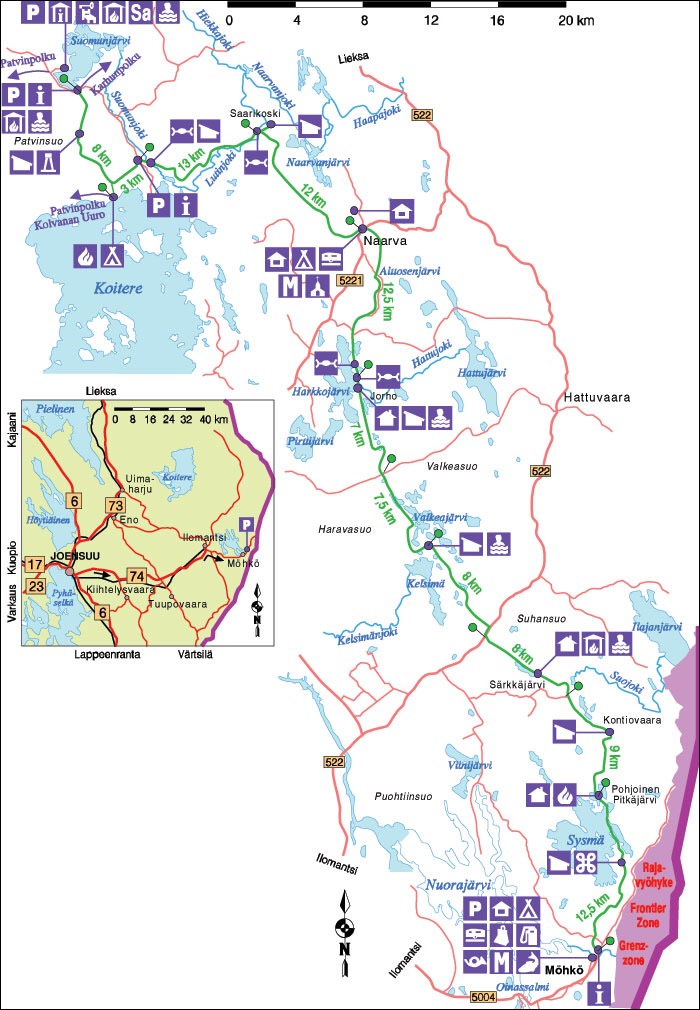

When I first started to plan attending the TSC conference back in February, I decided to see a bit of Finland as well. I would have loved to visit Lapland but expected that in June, I would likely be postholing through wet snow. So I opted for the Susitaival Trail further south. I completed the 100 km route over 4 1/2 days. Here’s a brief report.

Itinerary

I arrived on 2 June, did a bit of last minute shopping, and stayed a night at the Hotel Torni.

3 June: Checked bag at hotel. VR train from Helsinki to Uimaharju via Joensuu, 490 km, 5:20 hrs. Taxi from Uimaharju to Patvinsuo NP, 40 km, about 1 hr. Hike from Patvinsuo to Majaniemi, 11.4 km, about 3 hrs.

4 June: Hike from Majaniemi to Naarva village, 24.5 km, 8:07 hrs.

5 June: Hike from Naarva to Kuarnisjarvi, 26.7 km, 9:23 hrs.

6 June: Hike from Kuarnisjarvi to Pohjoisen Pitkäjärven Autiotupa (hut), 24.3 km, 9:28 hrs, including 1:30 hr nap at Sarkkajarvi.

7 June: Hike from Pohjoisen Pitkäjärven Autiotupa to Mohko village, 12 km, 3:51 hrs. Lift to B&B near Ilomantsi.

8 June: Bus to Joensuu, VR train to Helsinki.

All in all, a trail of middling quality. No views to speak of (unlike the Rockies) and the discontinuous nature of the trail, broken up by logging roads and clear cuts, made it somewhat unaesthetic. I had some rain the first two days of the trip, and it cleared up after that.

at the end of the Susitaival Trail in Mohko

Lots of evidence of elk (droppings), beavers (chewed trees), cuckoos (birdsong), and I saw grouse and herons a couple of times. Apparently there are still wolves and bears in Karelia, but no reports of bear attacks in the last 100 years and I saw no bears or wolves in 5 days. I suppose the ones who have survived hunting shy away from humans. But lots of mosquitoes kept me company each day.

Location

The trail is in Karelia, the easternmost province of Finland and runs south from Patvinsuo National Park to the small village of Mohko, which is a scant 3 or 4 kilometers from the Russian border. There is no public transit to Patvinsuo NP, so I took the train to Uimaharju and then a taxi (69 euros) the 40 km to the park.

There is no bus to or from Mohko, except the school bus to Ilomantsi. But luckily the Mohko museum attendant very generously offered to drive me to a B & B (35 euros/night) near Ilomantsi. From there, I caught a bus to Joensuu, and then a train back to Helsinki.

Terrain

Open Forest

Most of the route is through mature open mixed forest – Scotch Pine, spruce, and birch ranging up to maybe 15m in height. There is little growth below these trees, just moss and low ground cover, so visibility in the forest is generally good. Elevations range between 150 and 250 m, so, unlike the Canadian Rockies, there there are no steep or long climbs anywhere on the route.

Swamp

The word “suo” means swamp in Finnish and Patvinsuo Park, as the name suggests, is largely just swamp. From the parking lot on the highway that marks the formal start of the trail, it’s all on boardwalk for several kilometres. There are shorter sections of boardwalk as far as Mohko, and generally they’re well built. Only a few short sections (20 m or so) have no boardwalk or just rotting planks. Where the boardwalk is in forest, it’s frequently wet and slippery, and even though I paid extra attention on these spots, my feet went out from me more than once, dumping me on my pack.

The word “suo” means swamp in Finnish and Patvinsuo Park, as the name suggests, is largely just swamp. From the parking lot on the highway that marks the formal start of the trail, it’s all on boardwalk for several kilometres. There are shorter sections of boardwalk as far as Mohko, and generally they’re well built. Only a few short sections (20 m or so) have no boardwalk or just rotting planks. Where the boardwalk is in forest, it’s frequently wet and slippery, and even though I paid extra attention on these spots, my feet went out from me more than once, dumping me on my pack.

Lowlands

Obviously close to swamp. In Finland, much work has been done to dig ditches, generally about one meter wide to drain the lowlands, presumably to make summer logging viable. Where the trail crosses a ditch, there is either no bridge, a rotted few poles that have fallen into the ditch, or a few greasy poes posing as a bridge.

Ridges

South of Naarva, much of the trail follows discontinuous low ridges, obviously to avoid the many lakes and swampy sections. Half-buried rounded granite boulders dot much of the ridgetops, so I assume the ridges are all granitic, eskers deposited by glacial forces during the Ice Age. Largely treed and low, they don’t afford any vistas to speak of and where they do, all one can see is more trees and more lakes.

Logging Roads

The trail occasionally follows logging roads for short distances. These ranged from modern graveled active logging roads with ditches to mere overgrown cart tracks through the forest. A good way to make time but unaesthetic nonetheless.

Cut Blocks

My least favorite part of the entire route: inaesthetic, difficult to walk through, and often hard to navigate. But logging is a big part of Karelia’s economy, and the Everyman’s Right guarantees that such conflicts will occur outside national parks.

Bridges and Ferries

Unlike the Canadian Rockies, Rivers in Karelia generally aren’t fast-flowing or rocky. But they do appear deep, which might be illusory since they are stained deep brown by iron deposits.

There are four pontoon ferries on crossings on the northern part of the trail, all equipped with a life ring, spare oar, and an anchor. A clothesline pulley type mechanism attached on each bank to a tree allows you to pull the ferry to your side of the river to embark and then pull yourself across.

Small creeks had no bridges or a few rotting and unstable tree trunks tossed across. Not impossible, just inconvenient. There were two or three larger streams with well-built bridges, as above.

Navigation

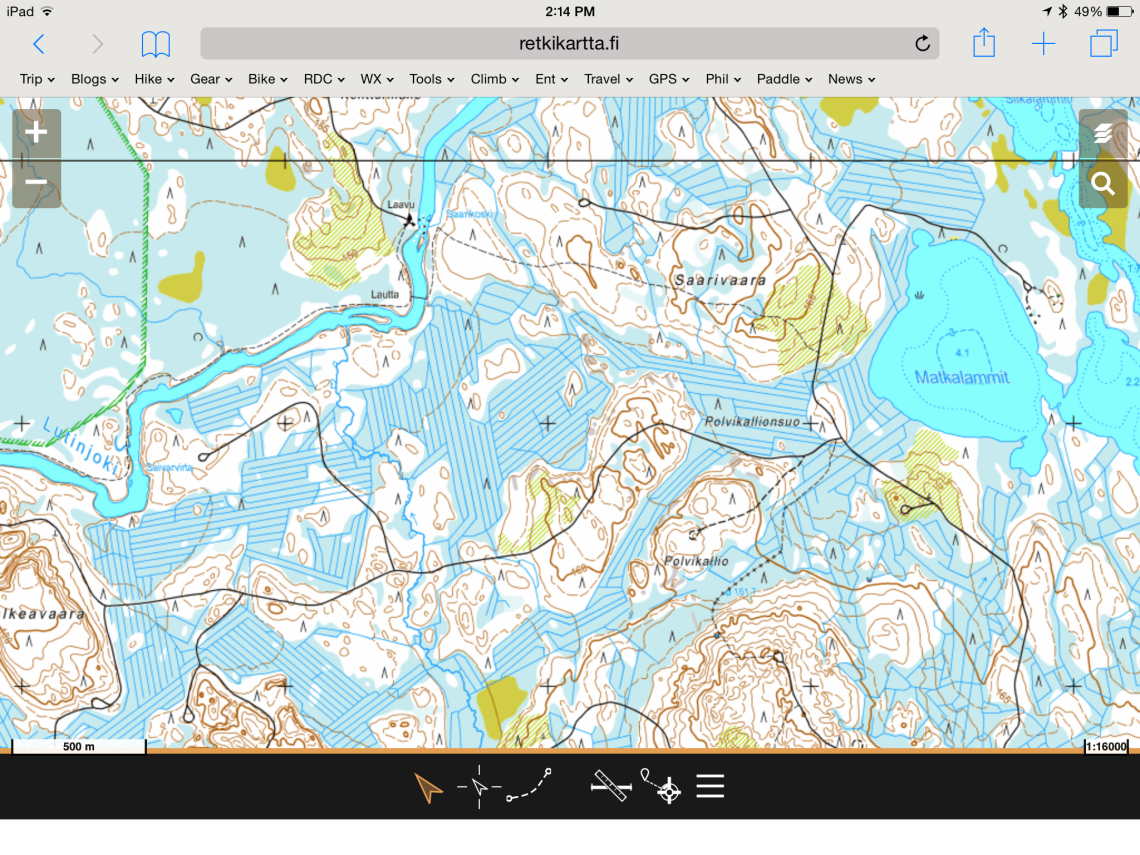

(iPad screenshot of the retkikartta app showing part of the trail. The light blue areas are swamp, the blue lines are drainage ditches.)

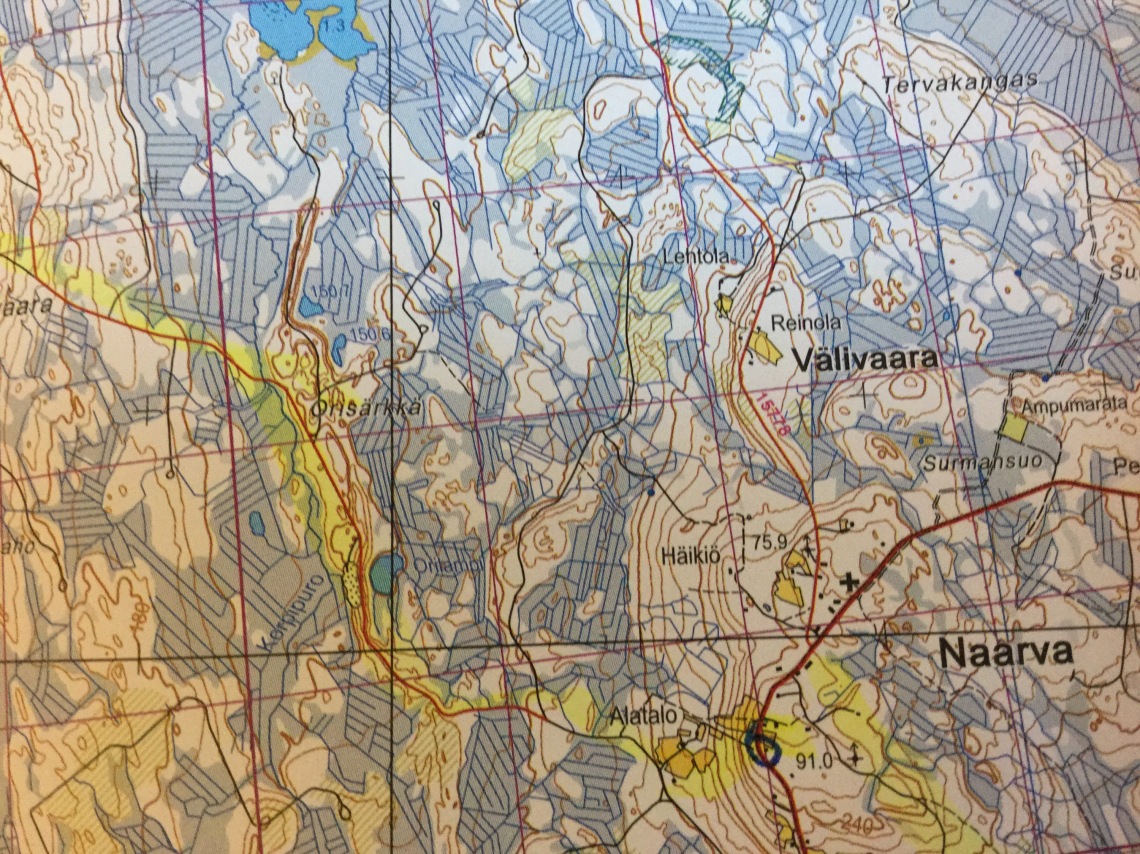

(Photo of 1:50000 topographic map)

Planning

I used:

- digitized map of Finland from OpenStreetMap.com (free download), including the trail and contours,

- Garmin Basecamp (free download) to view the OpenStreetMap map, route, and tracks

- the retkikartta browser app (free) which shows all topographic detail, and

- two GPS tracks downloaded from the web (free)

- two excellently detailed 1:50000 topo maps (Ilomantsi P611 and Hattuvaara P612) from karttakauppa that covered the entire route except for a short section through Patvinsuo Park. Best of all, the shipping was only 2.90 euros to Canada!

I then loaded the entire route on my Garmin Dakota 20 GPS. In retrospect, all a bit of overkill, but I enjoy this sort of trip planning.

In The Field

Trail sign at the Patvinsuo Park interpretive centre

The route is generally very well marked. Signs mark almost all intersections with roads. On the trail itself, trees are dabbed with orange paint alongside the trail. Where there are no sufficiently mature trees, orange paint spots on rocks, stumps, or 2″x2″ posts mark the trail.

Note orange paint spot on tree behind me.

The biggest difficulty I encountered was on logging roads. Where the trail intersected the road, take a moment to see if goes straight across, or to the left or right. And watch for blazes that mark which fork of a road to take or where the trail leaves the road. If necessary, consult your map or GPS to confirm your location. The temptation is to just walk down the road and not pay attention to navigation. Two or three times I had to backtrack 100m or so because I wasn’t paying attention.

Camping

typical laavu

one of several huts on the route

A well-appointed picnic shelter

A well-appointed picnic shelter

The Everymans’ right in Finland means that one can walk and stay overnight almost anywhere, including private land, without the owner’s premission, subject only to a few common sense restictions designed to allow the landowner to enjoy the use of his/her land. So different from Canada, where landowners jealously guard against trespassers and even national parks require fees, reservations, and permits for backcountry camping.

But there are complications. Nothing in the legislation precludes a landowner from logging a well-used and popular trail. A system of national parks protects land far more effectively. And while in theory, one can camp anywhere, most people will want a flat, clear site with potable water nearby. As the cynic says, pick any two. I saw only one or two truly random campsites on the entire trail.

But there are a dozen or so laavu (log cabin style lean-tos) and huts along the trail, all free for use. Each is well-marked on maps, and generally each site also has a fire pit, water source (a well or lake), a wood shed stocked with firewood, saw, and axe, a picnic table, and a pit latrine. Many are close to roads, and if so, also offer bins for garbage, recycling, and even composting. Just as in Canada, one encounters a few blackened pots, mattresses, a blanket or two, and abandoned food in the huts. But generally, the huts and laavu are clean, well maintained, and show no sign of vandalism by partiers.

Equipment

Some experts recommended heavy boots and carrying a 75 liter pack, snake bite kit, belt knife, and axe. So I didn’t.

Some experts recommended heavy boots and carrying a 75 liter pack, snake bite kit, belt knife, and axe. So I didn’t.

Instead, I used exactly the same equipment I use in the Canadian Rockies: Tarptent Moment (900g), SMD Swift pack with belt, belt pockets, and light frame (800g), Enlightened Equipment quilt good to +3*C (500g), Exped Synmat (1000g, a temporary replacement for my UL Synmat until I get a warranty replacement), 800ml MSR titanium pot (123g), MSR Microrocket stove (73g), Esbit folding titanium spoon (17g), first aid kit, repair kit, extra clothes, 800g of food/day, 2l Platypus water bladder, trail runners, and so on. I picked up a 100g butane canister and some cheese in Helsinki.

Historical Context

When I stared researching Karelia, the first thing I discovered is that the area was the site of many battles during the Winter War. So I took along William R. Trotter’s riveting A Frozen Hell to read on the trail, but found it so compelling I had almost finished the book before I started walking.

Finland, perhaps the least known of the Scandinavian countries, was for centuries ruled by Sweden. Later, they became a Russian colony and only achieved independence during the Russian Revolution, when the Soviets were too preoccupied with more pressing nternal affairs to notice Finland’s unilateral declaration of independence. In 1939, Stalin declares war on Finland, based on the absurd claim that the tiny country was about to invade a much more massive and better armed Russia. Stalin’s hope of victory was fueled by three assumptions.

First, Finnish peasants and workers would unite with Soviet troops to overthrow the right wing regime in power. There had been a brutal civil war a couple of decades before, wherein conservatives (Whites) had crushed a communist uprising by the Reds. 18,000 people died and there were atrocities commited by bth sides. Resentment still smoldered after this bloody conflict, but in the end, Finnish nationalism was the stronger motivator.

Second, Stalin thought he could sweep across Finland as Hitler had blitzkrieged his way across Poland. But the steppes of Poland are far more conducive to tank warfare than the forests of Karelia, which have few roads. And Stalin had purged his officer corp, suspecting disloyalty.

Third, the Finns had no air force or well equipped army to speak of and the Allies would not help them, even though they might wring their hands a bit. This was the only assumption that proved true.

mock-up of Finnish soldier during the Winter War. Military Museum.

The war lasted three months over the 39-40 winter. The Finns lost perhaps 50,000 troops, but the Soviet invasion ground to a halt after losing perhaps 250,000 troops and much of their armor. Many of the battles were so lopsided, Finnish soldiers wrote later that they felt pity for the vast number of Russian soldiers they slaughtered, many of whom had little clear idea why they were fighting, or even where they were. Some thought they were advancing on Helsinki, hundreds of kilometers away.

Famously, the Finns relied on skis and winter camouflage to surprise Russian locations. They buried their bunkhouses underground and protected them with barbed wire, which they then buried in the snow. Where they didn’t have anti-tank guns, they relied on Molotov cocktails to immobilize tanks.

Point of view from a Finnish machine gun bunker in Winter War. Military Museum.

Finland was forced eventually to sign a peace agreement with Russia. Within a couple of years, they again were at war with the Soviet Union (the Continuation War), this time with German help (arms and food) as part of Hitler’s Operation Barbarossa to invade the Soviet Union. This time the Finns were trying to regain land lost in the Winter War. As a result, the Allies declared Finland a co-belligerent, and declared war on the tiny nation. As part of a peace agreeement signed with the Soviet Union, The Finns promised to drive out German troops from Lapland, and this was the Lapland War.

As I drew closer to Mohko, I noticed a 2m wide depression at the top of a ridge. Then three or four more, spaced out 10m or so. A few kilometres later, I saw the same arrangement. Too seemingly arranged to be natural. I wondered if I was walking through an old battleground. It was a chilling reminder of a past that still affects many Finns. There must be hundreds of Russian bodies and tonnes of military equipment laying forgotten in the forests, swamps, and bottoms of lakes in Karelia.

These conflicts still leave their mark on the Finnish psyche. All men still have to serve a minimum six month period in the army when they turn 18. One Finn, who reported doing a lot of skiing in his military service, wondered about the usefulness of the exercise. He thought the Finns in WWII were far tougher than the average modern conscript, and, anyways, the nature of war has changed. But given Russia’s recent invasion of Ukraine, some degree of fear may still be justified.

Retrospective

As I mentioned, the terrain in Karelia is less spectacular than the the terrain in the Canadian Rockies – but maybe we’re spoiled.

Nonetheless, after seven months, what I do remember most about the Susitaival Trail is the incredible I help I received from Finns everywhere, even when they were unsure of their own ability to speak English. (The only Finnish sentence I knew was ” I don’t speak Finnish” and I managed to ruin that one sentence every time.) When you’re in a foreign country and don’t speak the language, any help is deeply appreciated.

So my sincere thanks go to many people:

Karelia Expert Tourist Service (now Visit Karelia) in Ilomantsi for their very informative website and prompt replies to my questions.

Mark at Backpacking North and Hendrik Morkel at Hiking in Finland who each gave me very good advice.

Markku Penttinen at the Koli Nature Reserve for answering my questions about Patvinsuo National Park.

Karttakauppa Finland (the official government map suppliers ) for producing excellent maps and charging very low shipping to Canada.

An unnamed attendant at the excellent Mohko Ironworks Museum (which I visited at the end of my hike – and it’s well worth a visit) who not only suggested a bed and breakfast near Ilomantsi, but phoned to confirm availability and since there’s no public transport from Mohko, even gave me a lift there when she finished her shift. From Ilomantsi, I was able to catch a bus and train back to Helsinki.

But most of all, Antti Rantaren of Long Distance Trail who offered lots of advice about travel in Finland and generously invite to his home for a sauna and dinner. I was happy to accept and I also met his lovely and vivacious girlfriend Maria. Thank you, Antti and Maria for being so hospitable!

Interesting post, well prepared and nice photos. I loved it. Thank You.

I and my wife love to hike in Lapland. Here is the third post which is just a start of our adventure. There are links to the next post:

North of the Arctic Circle 3.

Have a wonderful day!

I really wanted to see Lapland, but I thought June was a bit too early. So I envy you!